Pioneers of Tropical Living: Singapore’s ‘Middle-aged’ Condos

June 20, 2023

Over my nearly 20 years of living in Singapore, the city has changed almost beyond recognition. I moved here as a teenager, when Sentosa had a few ramshackle beach bars and Orchard Road had a huge green space where ION now sits.

Of course, change is the only constant in Singapore and other Southeast Asian countries. Growth is so rapid that the city struggles to keep up, and the default setting is to tear down the old and rebuild—newer, denser, though often with smaller unit size. In doing so, however, something intangible in the fabric of the city is lost, a core part of our architectural identity. Colonial-era architectural heritage is recognised and preserved, but the iconic buildings of the post-war era, crafted by a legion of local architects pioneering a new tropical style, too often fall through the cracks.

For many long-term residents like me, these are the buildings we call home. Perhaps it is nostalgia, or perhaps the ones who stick around are not those on shiny expat packages, but the older, first-wave condominiums are often where you will find this group, mixed in with the multi-generational families of original owners or early buyers. These developments are something of a cult housing niche. They are not shiny, or pretty, and often the maintenance is fairly haphazard, but they make up for this with space, a sense of community, and the opportunity to live as though you are actually in the tropics.

I have lived in my current condo, built in 1987, for eight years. Yes, there is always something leaking, and until recent re-wiring, our power would often cut out in a thunderstorm (no rare event in Singapore). But we live with doors and windows thrown wide open to capture the three-way cross-breeze, rarely using air-conditioning, and we have the precious commodity of space.

The thick concrete walls insulate us from the neighbours; we look out over a lush green estate, and beyond to the dense forest of the central catchment; on the balcony, we feel as though we are perched far above the world, sheltered yet open to the elements. This is the luxury of a building designed for the tropics, and this is what is lost when we do not consider these developments as valuable built heritage.

THE RISE OF THE CONDOMINIUM

Just 40 years ago, the condominium was a completely new housing paradigm. They were originally conceived to fill a gap in the market between private landed properties and public apartment blocks. Architects and developers saw the need for greater density and a shift to high-rise living, but needed to create a model that would attract a market used to the privacy and space of private housing.

Singapore was one of the earliest markets to respond in the 1970s, followed by Bangkok in the 1980s. With the success of these early pioneering cities, others such as Jakarta, Manila and Ho Chi Minh City joined the shift to high-rise living in the decades that followed.

Parallel to these market forces, the culture of design in Asia was undergoing a shift. The post-war years had seen waves of political independence and economic growth across the region. While the 1950s and 1960s still saw design dominated by foreign architects, by the 1970s and 1980s a generation of locally-born designers trained overseas had returned and were ready to shape their growing cities for the modern era. This meant taking what they had learnt of modernist design and adapting it to the local climatic context—driven by the primary elements of shade from the sun, shelter from the rain, and capturing cooling winds.

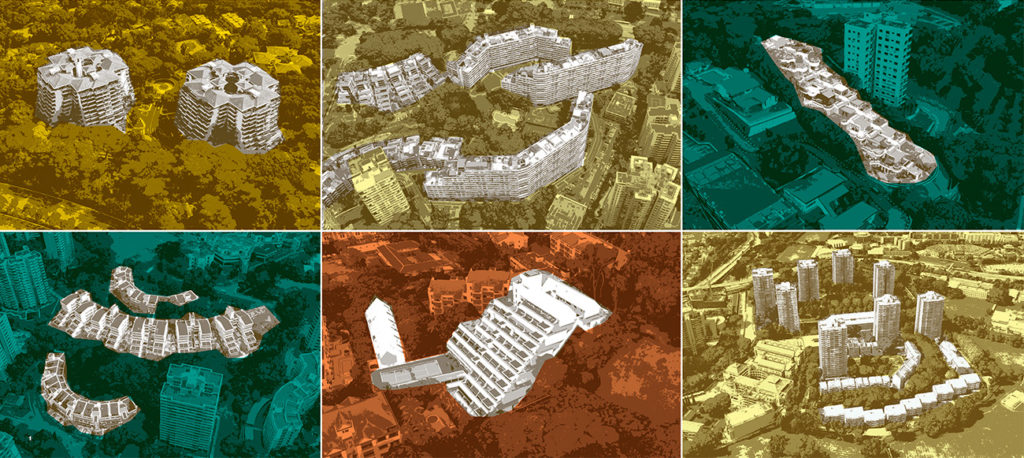

Immersion in greenery

Many developments are set in large, landscaped estates, with curated views of greenery from all units. Braddell View in Singapore (1981), although it follows a simple tower-block model, leans heavily on the estate greenery and the varying topography of the site to mitigate any feeling of density. At the ground plane, it is easier to get lost among the sloping lawns and trees than to identify the route to the next block. The point-block form also limits the overall mass of each tower and ensures privacy for each unit by limiting overlooking. Pandan Valley (1978) is another classic example, where the buildings are arranged around the perimeter of the site, facing inwards towards extensive lawns, a water body, and large trees that shade and create a feeling of immersion within dense vegetation.

Cascading form

First appearing in Pandan Valley, the stepped or cascading form is one of the most iconic and replicated features of this era. Interestingly, it is also one of the most enduring built forms, reappearing in modern architectural design as a way to mitigate building height and integrate greenery at multiple levels. In Singapore, this appears in the likes of Pine Grove, The Palisades, Pepys Hill, Mount Faber Lodge, and can even be seen in the softer, sweeping form of The Arcadia (1983). These developments typically have deeper and wider balconies designed to replicate a small garden.

READ MORE: Dive further into Asia’s modernist gems

[This is an excerpt. Subscribe to the digital edition or hardcopy to read the complete article.]

Heather Banerd is an urban and landscape designer, and freelance writer on the subject of sustainability. Based in Singapore, she has a background in architecture and is a graduate of the MSc Integrated Sustainable Design programme at the National University of Singapore. In her work, she strives to create meaningful, ecocentric urban spaces that will contribute to building a sustainable and self-sufficient future.

Related stories:

Architectural Restorations for Remote Countryside Regeneration in Hong Kong

The FuturArc Interview: Dr Johannes Widodo

The Old Alley’s Way of Life: Architecture Office in Hao Sy Phuong, Vietnam

Read more stories from FuturArc 2Q 2023: Old is Gold!

1 Building Construction Authority. (2010). Existing Building Retrofit. Singapore: Building Construction Authority; https://www.bca.gov.sg/greenmark/others/existingbldgretrofit.pdf

2 Gene, N. K. (2021, April 16). URA to study how to give Singapore’s ageing modernist buildings a new lease of life. Straits Times.

3 Urban Redevelopment Authority. (2020, October 9). Supporting the conservation and commercial viability of Golden Mile Complex. Retrieved from Urban Redevelopment Authority: https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Media-Room/Media-Releases/pr20-28#:~:text=In%20response%20to%20these%20challenges,the%20conserved%20building%20be%20sold.

4 Ang, H., & Chew, H. (2023, March 19). ‘We don’t know where we will go’: Tenants and visitors say their last goodbyes to Golden Mile Complex after 50 years. Straits Times.

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues.

Previously Published Main Feature

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older commentaries.