Rahul Srivastava and Matias Echanove

May 26, 2018

HB: The scope of work you undertake is really wide-ranging, from affordable housing and neighbourhood plans to studies, exhibitions and publications. How do you determine which projects to undertake? Is there a specific goal or objective behind your work?

ME: We are interested in neighbourhoods—how they grow, how they are shaped internally by the people living in them, and externally by everything from economic activities to history. You need to understand the dynamics at work—cultural dynamics, community dynamics, caste in the case of India—and the activities taking place before you can begin to work in a place. Dharavi has always been a fascinating place, and we learn a lot through working here. It’s a place that lets you see what happens when there is no planning, no architects and no engineers. Space is entirely shaped around communities and activities, and so we developed an approach based on our experience in Mumbai working with local actors and communities. In our practice, we work at different scales, for example, we can look at how to marginally improve people’s lives by designing the very small details of a house like staircases, stalls for vendors, and so on. But at the same time, we can do architectural projects, and also be involved with neighborhood plans, all simultaneously. Architecture is one entry point that we find very exciting, but the scale and entry point don’t matter as long as we can find ways to work in the local economy, with local actors.

RS: Our activities are also framed by research projects we choose to do, so we’re keeping track of what is happening around us in terms of economics, politics,

HB: You initially began practising in Mumbai, specifically Dharavi, but have since expanded to an office in Goa, and working on projects around the world. How does your approach differ across such diverse contexts?

RS:

ME: An important aspect of creating and maintaining this network is that people actually move from one place to the other. When we start working in a specific locality, we like to do a week-long workshop, where people come from all different chapters to participate. As they are familiar with the method and approach, they can plug in super easily and each brings their own experiences to the table. Then sometimes, for example, the Bogotá team comes here for a few weeks; sometimes we go there. So that’s also the way the network of the collective is kept alive. Our practice in Dharavi is like an anchor, where people become part of the network and then go back to their home city and work on it. Recently, many of us went to Geneva for a workshop, from Mumbai, Seoul, Montreal

RS: Geneva is a special office because Matias has his own personal connections there, while activities in Goa emerged because I happen to live half my time here. Many of our projects will emerge because people will ask us questions about what we are doing, and through our responses, we start developing dialogues and practices. In Goa, there has been a substantial increase in the slum population, and so naturally people are concerned, and they come to

ME: In Geneva, we’ve been quite lucky to be able to work with the government. At the time we started there, about two years back, there was a shift in the urban planning process and participation of residents became compulsory, so they were looking for help in that realm. There was a lot of discussion about participation but very little real practice. Then, most participatory practices that existed before in Geneva—and still in many cities around the world—are mostly round-table with sticky notes. We completely exploded that format. Our participatory process is much more about creativity: bringing people from the

people from outside and challenging what we know, bringing in new ideas, and trying to innovate in the process. In Geneva, these kinds of projects come as mandates from the government, and in Seoul, there is also a

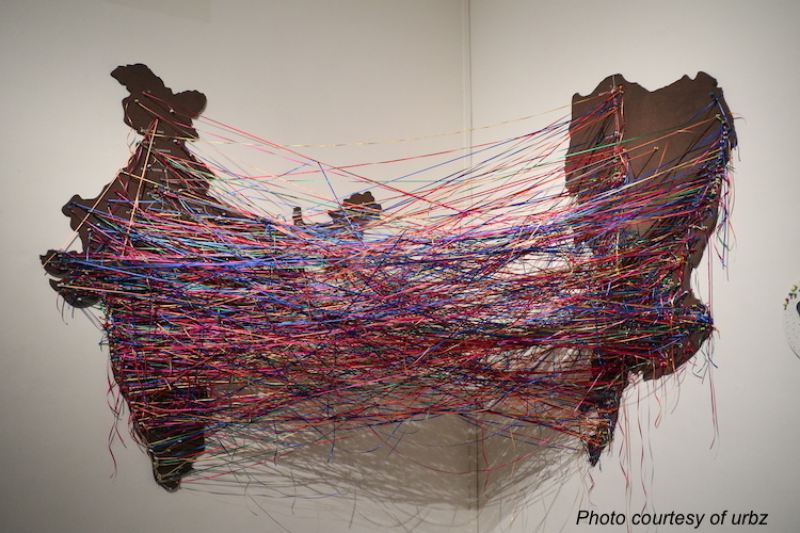

Installation at the Dr. Bhau Daji Lad Mumbai City Museum, Mumbai 2017. Visitors were asked to pin a thread connecting their native village to their neighbourhood in Mumbai. These connected maps show the dense network of connections that exists between Indian cities and villages.

HB: You’ve studied and written about the parallels between Dharavi and Tokyo’s mixed-use neighbourhoods that developed organically following World War Two. Why do you think these areas have turned out so differently while following similar methods of development? Can these neighbourhoods be seen as models for high-density urbanism?

ME: Rather than seeing Dharavi as a model of high-density urbanism, we see it as somewhere where the processes at work are very obvious. These processes are also at work in many other places, which are now considered to be informal, or slums, though they may not be as clear. From these, we observe that mixed-use, high-density, low-rise

HB: How do you think cities can act on this, and encourage more diverse development?

ME: We feel that really starting to understand the use that people are already making spaces is really important. In some cases, it’s quite obvious because those uses are already expressed clearly, and in some cases it’s something that needs to be discovered because it’s not so easily visible. We always like to give the example of Steve Jobs’ start-up in a garage, which is basically an illegal use of residential space, yet this creative use of underused spaces is exactly what we should be looking at when we’re designing when we’re planning. So drawing from the use, from existing activity, is for us the core of the approach. The best way of doing this is, first of all, to observe but also to let people express themselves, in the participatory process. Participation for us is not just some kind of moral or political imperative—it can actually help us design better. It can also highlight flaws in existing planning processes. In one of the projects we are doing now in Geneva, a plan is emerging based on the way the residents want to use the neighborhood that is complicated to implement using existing planning frameworks and tools. This has led to very interesting interactions with the municipality and the state, who are quite open to thinking about how they need to reform or work around the way they have been planning so far.

RS: I also think we need to have new models of financial investment in urban development. Right now, there is

ME: A term we coined recently to express this is “excel sheet urbanism”—planning based on regulatory constraints and conventional financial models, where development is focused on mono-functional blocks, because this is what investors understand. Nobody wants to go to the trouble of understanding how to finance and insure plans for low-rise, high-density, mixed-use development. It’s perceived as too complicated, but we don’t think it is. The state can be an important

RS: Ultimately the way we work in

HB: How do you see urbz evolving in the future? Do you have specific goals you want to achieve?

ME: We want to consolidate the collective, especially in terms of exchange of experience and exchange of methods, to see what works and what doesn’t work in different contexts and why. We’d also like to work on developing the

Ideal house for Dharavi designed by a builder who lives and

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues!

Previously Published FuturArc Interview

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older interviews.