Reclaiming Immaterial Spaces

September 26, 2020

We are inspired by Donna Haraway’s subversive understanding of ‘fiction’, as an active principle in a world of possibilities, about looking forward, as a stimulus to act—as opposed to ‘fact’, as something that belongs to the past, a reference to that which has already happened. It symbolises our tilt towards action and interactions in the spatial realm, but with a strong dose of imagination. A love for the here and now, and an irrepressible drive towards the boundless potential of place.

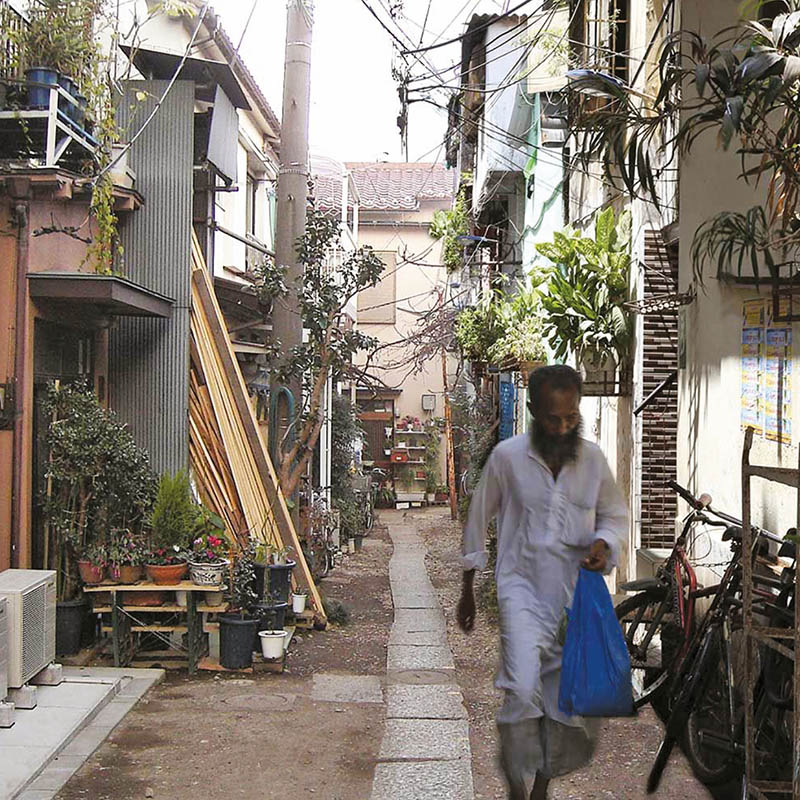

In 2008, we used a fictitious image, an amalgamation of two disparate streets but with a similar grammar—one from Dharavi in Mumbai and another from Shimokitazawa in Tokyo—to kick-start a workshop in a fishing village in Koliwada, Dharavi. The idea was to go beyond the apparent, relate to what exists with fresh eyes, work with the potential and the people of the locality, and challenge the common gaze of negativity that had reduced the neighbourhood to a convenient but inaccurate label—a slum.

Localities are infused by the inhabitants who make them—their biographies, histories, skills, memories, impulses and of course, their physical selves. They create worlds in all kinds of contexts. They emerge from the flows of people, information, images and ideas. They are always (at once) real and virtual, rooted and mobile, here and elsewhere, cohesive and fragmented, parts and wholes.

Mumbai, India, 26 May 2020: Migrant workers with their families stand in queue to board a bus that takes them to a railway terminus for boarding a special train back home during a nationwide lockdown (Manoej Paateel/Shutterstock.com)

Post-COVID-19 lockdown, what we see happening is that locality has become spatially reduced and virtually expanded at the same time. Since the full- and part-time inhabitants of Dharavi (that includes us) live in both virtual and face-to-face contexts, even in ordinary circumstances, dealing with a greater reliance on the virtual is not treading on unknown ground.

If anything at all, the crisis helps us understand and prepare for the fact that localities may become more consciously virtual as they are spatial. Urbanologists will work in and on the virtual (which, as we discussed above, includes the mythical and the fictional), along with all the technological and creative tools available.

Maybe the best way to deal with the pandemic—and the way it has locked us down—is to reclaim the immaterial space that connects us all to the places we care about.

This is a photoshopped image. On the left is a slice of a street in Shimokitazawa in Tokyo and on the right is one from Dharavi in Mumbai. They are fragments of incrementally grown neighbourhoods with their characteristically low-rise, high-density, human-scale development. The composition highlighted the universalism of an urban form that transcends labels. Shimokitazawa is a trendy urban quarter in Tokyo, celebrated for its whiff of the old city, while Dharavi is trapped in the narrative of a slum (photo by Matias Echanove).

References

Appadurai, A; Modernity at Large, 1996, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, London

Echanove, M & Srivastava R; The Slum Outside, 2014, Strelka Press, Moscow, London.

Haraway, D; Primate Visions, Gender, Race, and Nature in the World of Modern Science, 1989, Routledge, New York.

Srivastava, R; The Unknown Firewalls in Shockwave and other Cyber Stories, 2007, Penguin, India, New Delhi.

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues.

Previously Published Main Feature

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older commentaries.