In Conversation with Yatin Pandya

January 27, 2018

NA : After your bachelor’s degree in architecture from CEPT University in Ahmedabad, what was the focus of your master’s programme overseas ? And thereafter, what made you come back and start off a career in Ahmedabad?

YP: I pursued higher studies in low-cost housing from McGill University in Montreal. What we studied there was also relevant to India as it addressed the universal issue of housing with three major concerns—how does one account for sociocultural appropriateness, frugal resources

Simultaneously, I was also interested in the vernacular habitat. There have been two references since I started my career, and as part of the Vastu Shilpa Foundation, we made efforts to evolve norms and standards that are indigenous and related to our context. I would begin with the traditional habitat, not for nostalgic reasons but because there are important lessons that they demonstrate purely by their performances. Despite harsh conditions in Ahmedabad, if we can build environmentally friendly physical spaces with adequate comfort, why can’t we learn from those principles today and develop them further instead of dismissing them, to rely entirely on high-energy intensive means of comfort? I also refer to squatter settlements that were derived by the people themselves. Built out of a severe resource crunch, they reveal needs and priorities better. Although deprived in terms of physical infrastructure, they express a habitat much closer to their lifestyles and day-to-day needs.

The second point of reference is timeless aesthetics: how a building performs over the years and withstands the challenges of time to not wear off from people’s memories and appreciation, like most of the ruins. Although functionally obsolete, these structures built in scarce resource conditions continue to be an exciting architectural space. So this quality of timelessness and sustainability has led me to delve into vernacular architecture. Even in Montreal and later at Vastu Shilpa, we derived lessons from these habitats as they have succeeded in bringing in sociocultural responses, greater interactivity and a timeless quality.

NA: Until recently, India was largely isolated from the world markets. Now, with globalisation and the integration of world economies, do you believe these lessons are appropriate in the current circumstances?

YP: I believe human behavioural responses have not changed for centuries. Today, we base our existence on technology that becomes obsolete in no time. We still go to the cinema even with the television at home providing over 30 channels; we prefer meeting people over the phone or video call right? Certainly, those are fundamentally more ‘human’.

Making a prototype independent of site, context and cultural lifestyle is rather regressive and strange. It lends tremendous burden on the user to maintain the entire mechanised infrastructure. Taking clues from centuries-old traditional pol houses with shared walls, we can possibly release congestion from our urban land by building only four storeys to consume the available 1.8 free space index (FSI).

I have learnt a lot from the pol house and traditional courtyard house typologies to contemporise the form of row houses with the front and back yards from the bungalow and street edges from the cluster. It brings light, ventilation, views with privacy and interactive edges, presenting a classic civic form to the city. There’s no denial of new technology; we are only recognising what is proven true performance wise and take it from there. Any development that bases its principles on these two equations—human to human (interaction and interdependency) and human to nature—has responded to the call of the environment, humanity and sustainability.

Human behavioural responses have not changed for centuries. Today, we base our existence on technology that becomes obsolete in no time.

NA: How do you see the idea of sustainability being accepted as an underlying principle today? More importantly, how would you demonstrate its development over the past few decades in India and otherwise?

YP: We are currently working on a book that demonstrates a study on contemporary Indian architecture where we have traced the so-called pendulum swing. In post-independent India, there was a collective euphoria of an independent nation and political thinking to ‘begin again’. Corbusier and Kahn were invited to plan our cities and suggest a way of living with brand new infrastructure and a modern image. That was a conscious denial of the past. The next decade or so traced the admiration of the first planned city and many such structures by the Indian masters that adopted similar grammar and aesthetics. Then about 25 years later, the late 1970s and 80s were to me better phases of the Indian architecture and built environment, when we enquired into finding local answers to infrastructure, poverty

This was the introspection age and an example is the work of architect Laurie Baker. His work in Kerala came to be

Unfortunately,

NA: How do you think the government policies in India are responding to the current need for sustainable living and building norms?

YP: Our policies in the recent past have been formed by a government that has

For instance, if instead of applying a mandatory 10- to 15-feet side margin on a plot, a reversed typology with internal margin was enforced, it would provide for a usable open space to the residents. Additionally, I feel a reverse by-law of

NA: Would you explain the position of professionals as role models in bringing awareness and advocating an appropriate way of living?

YP: A large majority of professionals have somehow been subjugated by the development patrons and haven’t been honest to the profession’s ethics. As a result, we have lost our faith value, (

| 1. Siting and location | 4. Elements of space making |

| 2. Form and mass | 5. Material and construction techniques |

| 3. Space organisation | 6. Finishes and surface articulation |

Any building, good or bad, demands architectural decisions based on these six aspects. Only when we understand the wider implications of these decisions would we be able to make informed choices and arrive at the resolutions. So the debate is not about shying away from the technological advancements but rather to let them play second fiddle and not hide architectural fallacies behind the façades of energy-intensive

technologies.

To bring awareness, the first and foremost is to provide the right value system during education. The second would be

NA: What is your opinion on the Green building movements in India and worldwide? What do they offer in terms of bringing people closer to a sustainable lifestyle?

YP: Green has become a fashionable word these days. Unfortunately, more often than not, it has remained a word rather than a

Green has become a fashionable word these days. Unfortunately, more often than not, it has remained a word rather than a colour. As a result, it gets interpreted in numerous shades.

NA : Your practice demonstrates a dedication towards raising awareness on Green architecture far beyond just the built environment. What standards or development norms have been evolved that can facilitate a change in the lifestyle of a wider audience?

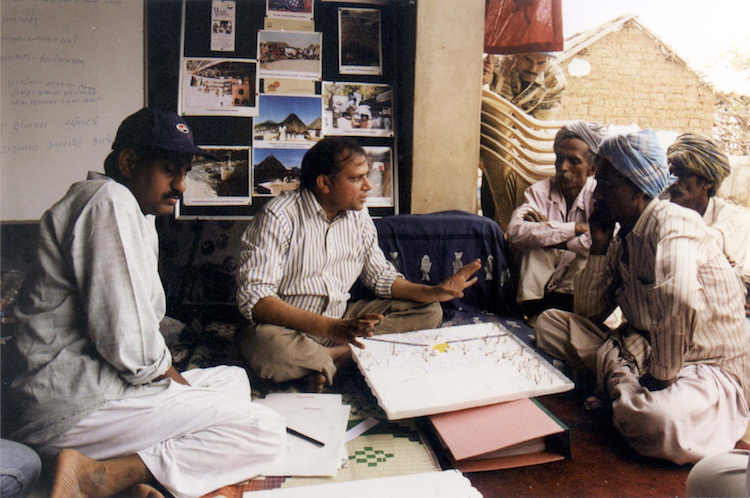

YP: Our practice is research-driven and for every project, we evolve local solutions appropriate to

For example, the Environmental Sanitation Institute that was built in 2004 is a holistically sustainable campus, from water harvesting and waste recycling to passive cooling and solar-active strategies, etc.; Manav Sadhna is about waste recycling as building components; Evosys is about eco-friendly interiors; and Karma is a stand-alone office building with multiple solar passive strategies, and so on. We have always documented our research and processes with actual figures for relevant application, which is handed out as monographs, free of cost to schools and colleges.

The project Ujasiyu was initiated to provide natural daylight and air ventilation in the dark and dingy spaces of slum houses of the urban poor. Simple, affordable, alternative solutions were devised and were installed in 140 houses in the slums of Ahmedabad alone in less than two years. As a participatory solution, it is in the progress to spread through many more settlements even outside of Gujarat. Through publications and academic

We firmly believe that sustainability is not a formula but a phenomenon that needs to find appropriate interpretations according to context.

NA: What are the things that inspire you?

YP:

The Pompidou Centre—not for its function because I would still get intimidated of going inside. What is unbelievable is the impact of its façade that has turned its surroundings into an active civic plaza! I don’t recall any contemporary building of being able to succeed in igniting such impromptu responses. It’s the way the building stimulates communication and gives people the liberty to make it their own. Likewise, there are many other examples that interest and excite me, including the jelly bean installation in Chicago by Anish Kapoor.

That intervention has turned the park into an absolutely amazing active civic space.

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues!

Previously Published In Conversation

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older interviews.