OCEANIX City: Keeping future cities afloat

June 15, 2022

As modern cities sequester people off into skyscrapers and dense living quarters on land, it might be easy to forget that two-thirds of the Earth’s surface consists of water—a necessity for life, but also an increasing existential threat based on recent heavy floods that disrupted major cities. While water is running dry in some cities, causing problems like land subsidence, it is rising rapidly in coastal lowlands due to climate warming, threatening the lives of millions around the world.

Take, for instance, the sinking city of Jakarta, where a quarter of the land is feared to be submerged by 2050; frequent floods in Venice that are accelerating building decay, up to the point where the structures may not survive into the next century; and Africa’s most populous city, Lagos, which is only 1 metre above sea level and is in danger of being completely submerged by 2030.

Some stopgap solutions against sea level rise have been devised and applied around the world, such as coastal walls and land reclamation. But not only do these solutions have a massive detrimental impact on ecosystems, they also tend to displace coastal communities in the process. Innovation is needed to bring forth viable and non-destructive systems, which entails rethinking cities that complement living with water, instead of fighting it. So, rather than investing resources to prevent sinking cities, we could make them float instead.

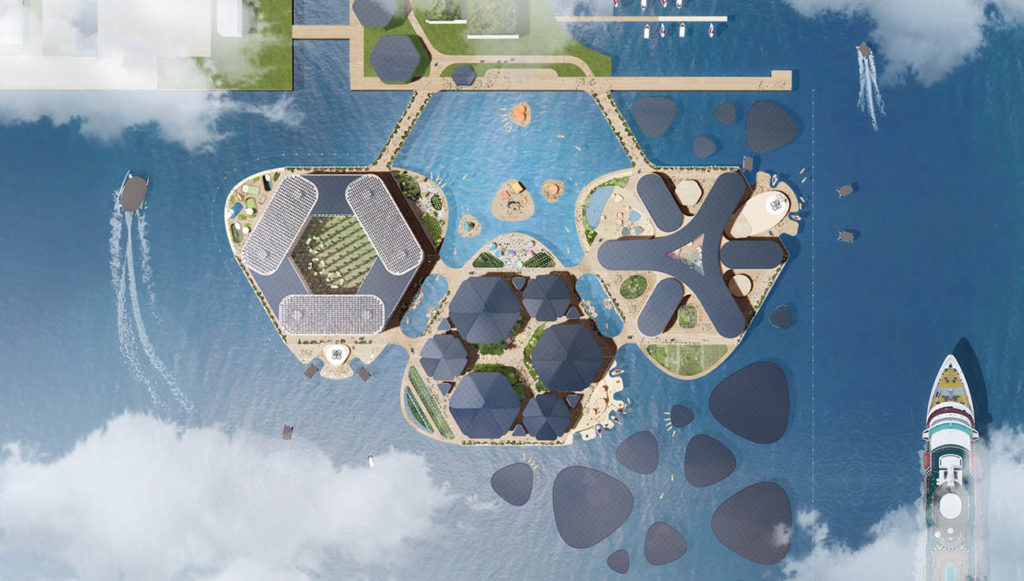

Visualisation of the platforms scaling along Busan’s North Port in stages

OCEANIX offers a promising framework for waterborne urbanism, having gained political support from transnational actors such as the UN. Time will tell if the experimental technologies can provide a more sustainable way of living—one that can be scaled to improve the resilience of coastal areas worldwide.

RELATED: News | Partnership signed to build the world’s largest sustainable floating city in Busan

A MODERN, CIRCULAR FLOATING CITY

Floating settlements are not new—aside from stilted structures that are a common part of vernacular riverside homes, there are waterborne villages such as in Halong Bay, Vietnam; Aberdeen, Hong Kong; and Uros, Peru, where the houses are afloat on boats or raft-like wooden structures. However, what would set OCEANIX apart is its prefabricated method to achieve economies of scale, the types of materials used, and application of modern technologies for a circular system.

Biorock base for habitat regeneration

The base of the floating platforms will use a material that would not disrupt the ecosystem—it could instead help underwater flora and fauna to flourish. Biorock has been widely applied since the 1970s for reef restoration. In its (since expired) trademark detail, Biorock is described as “artificial reefs and wave barriers made from metal containing live organisms that grow on or in the structure including coral, oysters, mussels, lobsters, octopus and fish”.4

Biorock starts out as a steel structure that is continuously charged with a safe, low-voltage electric current. This prevents corrosion while encouraging the growth of a solid limestone rock structure, which is two to three times stronger than ordinary concrete. It is also known as ‘seacrete’.

Food production, waste collection and processing

With the goal of creating a zero-waste society, OCEANIX will apply a closed-loop system that processes organic waste into energy, agricultural feedstock and compost. Aside from fostering ‘3D ocean farms’ consisting of seaweed and shellfish grown on water columns, food will be sourced through farming in greenhouses, aeroponics and aquaponics. The diet will be largely plant-based with seafood protein, moving away from carbon-intensive red meat.

Pneumatic tubes that are designed for marine conditions will be used to collect waste from between buildings. Sewage will be treated in three facilities: a waste water treatment plant within the base; a treatment swale on the platform; and a floating algae filtration system (with the microorganism cultivated by a photo-bioreactor that harnesses sunlight). OCEANIX does not yet detail how these systems will connect to one another, but there have been precedents for their application separately, such as an algae photo-bioreactor in Daphne, Alabama.

[This is an excerpt. Subscribe to the digital edition or hardcopy to read the complete article.]

PROJECT DATA

Project Name

OCEANIX City

Status

In Progress

Site Area

6.3 hectares (OCEANIX Busan)

Client

OCEANIX

Lead Architects

BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group); SAMOO Architects and Engineers (Samsung)

Partners-in-Charge (BIG)

Bjarke Ingels; Daniel Sundlin

Project Leaders (BIG)

Alana Goldweit; Jeremy Alain Siegel

Team (BIG)

Andy Coward; Ashton Stare; Autumn Visconti; Bernardo Schuhmacher; Carlos Castillo; Cristina Medina-Gonzalez; Florencia Kratsman; Jacob Karasik; Kristoffer Negendahl; Mai Lee; Manon Otto; Terrence Chew; Thomas McMurtrie; Tore Banke; Tracy Sodder; Walid Bhatt; Will Campion; Yushan Huang; Ziyu Guo

Collaborators (OCEANIX Busan)

Prime Movers Lab; Arup; Bouygues Construction; Helena; Korea Maritime and Ocean University; MIT Center for Ocean Engineering; Mobility in Chain; Sherwood Design Engineers; Center for Zero Waste Design; Transsolar KlimaEngineering; Global Coral Reef Alliance; Olafur Eliasson and Studio Other Spaces; Dickson Despommier; Agritecture; Greenwave

1 https://unhabitat.org/roundtable-on-floating-cities-at-unhq-calls-for-innovation-to-benefit-all

2 FuturArc 1Q 2022: Housing Asia

3 https://www.futurarc.com/happening/prototype-for-a-sustainable-floating-city-to-be-built-in-busan/

4 https://trademarks.justia.com/761/66/biorock-76166682.html

Read more stories from FuturArc 2Q 2022: New & Re-Emerging Architecture!

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues.