Home for Marginalised Children

February 6, 2023

In line with our ongoing design competition FuturArc Prize (FAP) 2023: Cross-Generational Architecture, we are highlighting projects along the theme for your inspiration. Click here to learn more about the brief!

⠀

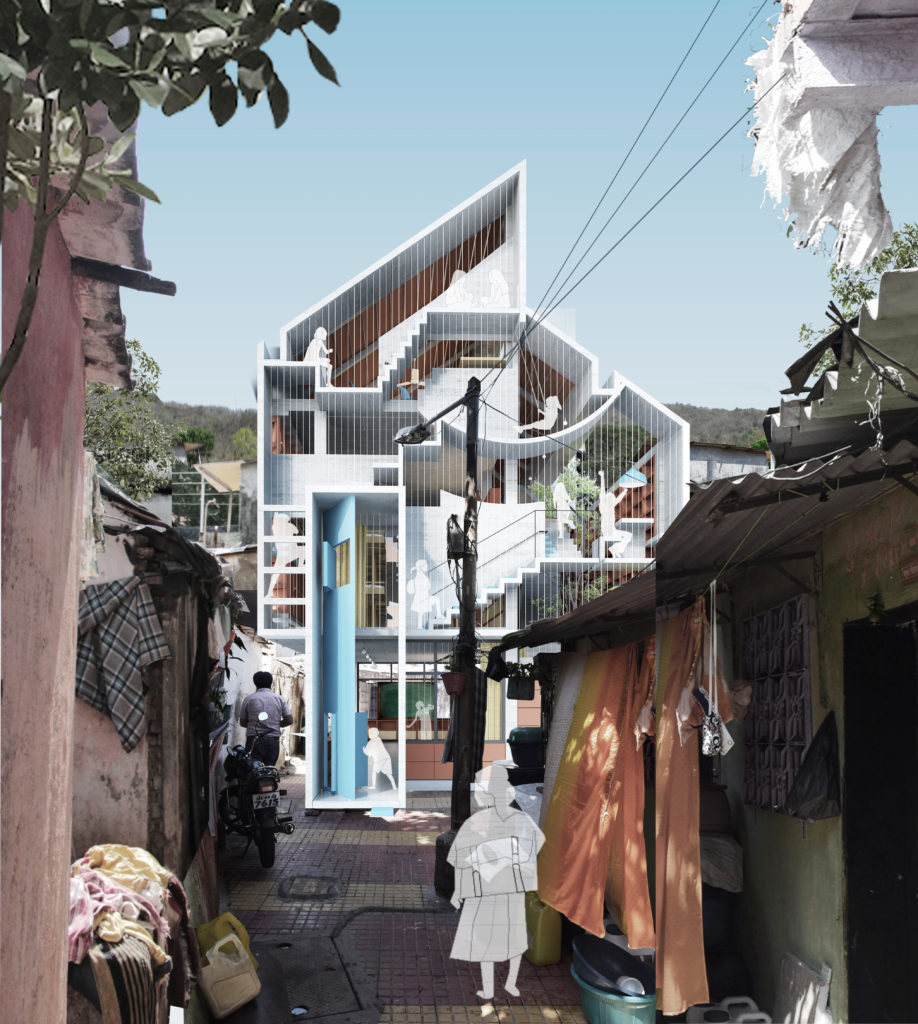

This project in Thane, India was established as a shelter for abandoned children in an informal settlement. It was designed by atArchitecture as a residence for around 30 girls, ranging from ages 3-16. The centre also functions as a community gathering space hosting events for senior citizens, women and infants. FuturArc correspondent Heather Banerd spoke to architects Avneesh Tiwari and Neha Rane, founders of atArchitecture.

HB: How did this project come about?

AT: Around [2014], we decided to use our practice to give back to society, so we approached a handful of NGOs in Mumbai, offering free architectural services. Our client, CORP, was one of those who responded.

Q: The awards jury nicknamed the project the White Rabbit because of the playful, whimsical feeling of the design, which is very much oriented towards the children’s experience—how did you approach this?

AT: This really arose from the project itself. When we went to the site for the first time and started interacting with the kids there, we noticed that most of the current space was actually occupied by storage, so there were 30 people in a 600- to 700-square-feet area with no spillover space. Because of the limited area, the kids were not behaving true to their age. Imagine being a kid, just sitting in one corner, doing nothing. This is what the project evolved from—we wanted to give them the freedom to act their age, to give them their childhood back.

Part of this is the idea that the users will transform the space. For instance, the elevation we designed will be completely different when it is up. As the façade is inhabited and interpreted by the users in their own way, it will take on its own character.

HB: So essentially, you want the building to act as a canvas, allowing the users to create their own space.

AT: Absolutely. The existing structure is only a small building with drywall and small openings. We wanted to provide them with freedom and privacy, as well as the ability to interact with the neighbourhood—the building should not show its back to the slum. So the two recreational areas become places of interaction, like the veranda of a house where the kids can play, sit, read, do whatever they like, while the façade interacts with the slum and becomes a part of the overall slum fabric.

HB: How did you find the community around the site? Were they receptive to the project?

AT: From our interaction with the administration and the caretakers of the slum, there is no problem. The current structure has already been there for five, 10 years now and everyone is ok with it.

NR: It is a community centre for the slum also. They wanted a sort of hall where they can conduct development training and activities for senior citizens. They are happy with the proposal, because the ground floor is open for community use. It functions as an old-age day care unit and a crèche, so kids can spend their time there while their parents work around the slums. Otherwise, the slum doesn’t have any place for children, so the structure enables this service.

HB: The project uses some interesting materials, such as terracotta—did you have a specific reason for choosing these?

NR: Terracotta is a traditional material, and the neighbouring slum has a small-scale terracotta industry, so we wanted to use local craftsmen to make these blocks to engage the community, so that the funding for the project goes back into the community.

HB: A major theme in the awards is replicability—the potential for these ideas to be expanded beyond a single project. How do you think this manifests in your project?

AT: If you look at the six design elements, they all originated from the challenges of the brief—the tight area, the needs of the users, the surroundings, and the weather conditions. So responding to these, we came up with the six elements, which are very much project specific. But, for instance, if a similar structure at a different scale is coming up in another slum, it could be replicated with a few tweaks here and there—depending on the new users and the immediate context of that particular site.

HB: So, you see the design principles of the project as the replicable element that can be applied in a different form on other sites?

AT: Correct.

HB: Beyond community engagement, what was your approach to sustainability? Did you intentionally set out to be efficient in water and energy?

AT: The water efficiency strategy actually grew out of the programme requirement. The client wanted to increase the toilet provisions from one to seven, so it made sense to install a rainwater harvesting tank to meet the additional water demand. We did this without compromising space by modifying the foundation. If the columns stand on an isolated footing, there is very little space left in between; however, retaining the soil on the sides and using a raft footing can add area at a nominal cost. This area is used for water storage. The water can also be used to irrigate the vertical façade planting. The energy strategy is also linked to cost efficiency. The courtyard enables natural lighting and passive cooling, while the terracotta louvres and recreational bands allow cross ventilation and shade the interior spaces. All of this reduces the operational energy load, which helps keep the building cost efficient. The project is not built upon only one single idea, but many different things coming together and acting holistically, so the project is sustainable in its entirety.

Originally published in FuturArc Mar – Apr 2018; click here to shop the issue.

Register for FuturArc Prize 2023: Cross-Generational Architecture exclusively from FuturArc App! Download now from App Store or Play Store!

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues.