Urban greening and architectural form: A Bird’s Eye View

July 10, 2018

The loss of green cover in cities is often discussed as an issue of human well-being. We speak of increased urban heat island effect, worsening air quality and the psychological discomfort arising from our separation from nature. These are important points, and critical to developing more liveable cities, but they overlook a crucial consideration: that green elements are also part of complex natural systems that support life in general, including species other than our own.

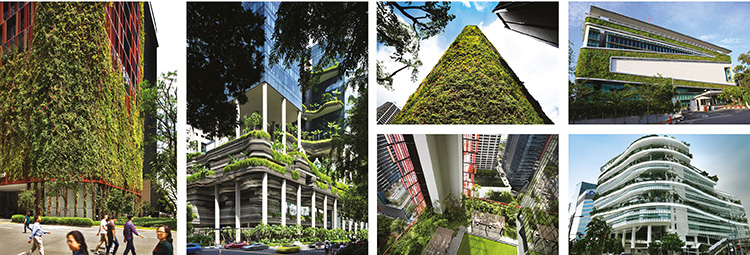

Of late, building-integrated greenery has become a widely accepted design strategy. Green roofs are popular as they offer added social space; green walls are liked for their visual appeal, creating a ‘wow factor’.

These strategies can be applied to any typology at any stage in the design process. In other words, they have little impact on early consideration of form. Architects like Ken Yeang and WOHA, however, have been exploring the potential of building-integrated greenery in reshaping conceptual form.

In Constructed Ecosystems (2016), Yeang lays out several strategies for incorporating greenery within recesses, voids and incisions. To link these with ground-level planting, Yeang proposes the concept of a ‘linear park-in-the-sky’, in which a vegetated strip can be mounted vertically onto the façade (DiGi Technology Operation Centre, Malaysia) or placed flat as a horizontal ribbon winding upwards around the building (Solaris, Singapore) to create continuity and connectivity.

WOHA’s use of greenery varies with each project; in many projects their design strives for green coverage that is more than the site area. In Oasia Downtown, Singapore, greenery is vertical planting on a second skin façade with patches on mid-level decks. In the PARKROYAL on Pickering, a high-end hotel development, the architecture is organised around cascading terraces acting as patches, supplemented by façade and podium planting.

Both WOHA and Yeang are explicitly interested in using building-integrated greenery to create habitats (patches) and pathways (corridors) for species movement. What is not yet understood is whether biodiversity, such as birds and butterflies, recognises and responds to this design intent, and whether one form strategy is better suited than another.

BIODIVERSITY-CENTRIC GREENING: RULES-OF-THUMB FOR URBAN INTERVENTIONS

by Dr Anuj Jain

The value of a vegetated patch is predicated on general principles of biodiversity in urban patches.

Communities of species common in urban patches tend to be urban adaptors, species tolerant of urban microclimates, noise and edge effects, and who are able to move and disperse in an urban matrix. Such species tend to be habitat generalists, and therefore common and widely distributed in urban landscapes. Increasing generalists is as valuable as increasing species diversity because they are responsible for the bulk of ecosystem services (Gaston 2010).

Patches serve two broad functions, according to size. Habitats, where animals live, feed and breed; and corridors, which facilitate movement between patches. While the design of each is highly dependent on context and species, a general rule is that habitat patches should be a minimum of 10 to 20 metres wide in order for small mammals, insects and lizards to form territories and resident populations. Some small mammals may need vegetation of 20 to 30 metres wide to constitute a habitat. Patches smaller than 10 metres in width tend to function as corridors. The relationship between habitat size and number of species is non-linear. It follows a power-law function (Diamond 1976), wherein a doubling in habitat size will more than double the number of species.

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues.

Previously Published Commentary

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older commentaries.