Switching coal plants to biomass cofiring is no magic bullet

March 23, 2021

Over the past year, Indonesia’s energy policy teams have devoted new resources to a plan focused on efforts to extend the life of PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara’s (PLN’s) coal-fired power fleet by switching to biomass cofiring. The plan focuses on leveraging PLN’s existing 18 gigawatts (GW) of coal-fired power plant capacity.

The planners are betting that they can slowly increase biomass power generation by cofiring, a strategy that would potentially extend the life of older and under-utilised coal units while at the same time claiming credit for increasing the renewable energy mix.

Important questions must be answered concerning the economic viability, feedstock supply stability and technical challenges associated with extending the life of Indonesia’s coal plants using cofiring, according to a new report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

In the absence of significant incentives, it’s impossible not to question whether PLN will be able to deliver cofiring without encountering technical and financial barriers.

“The cofiring plan will require nothing less than the creation of a large-scale biomass industry.”

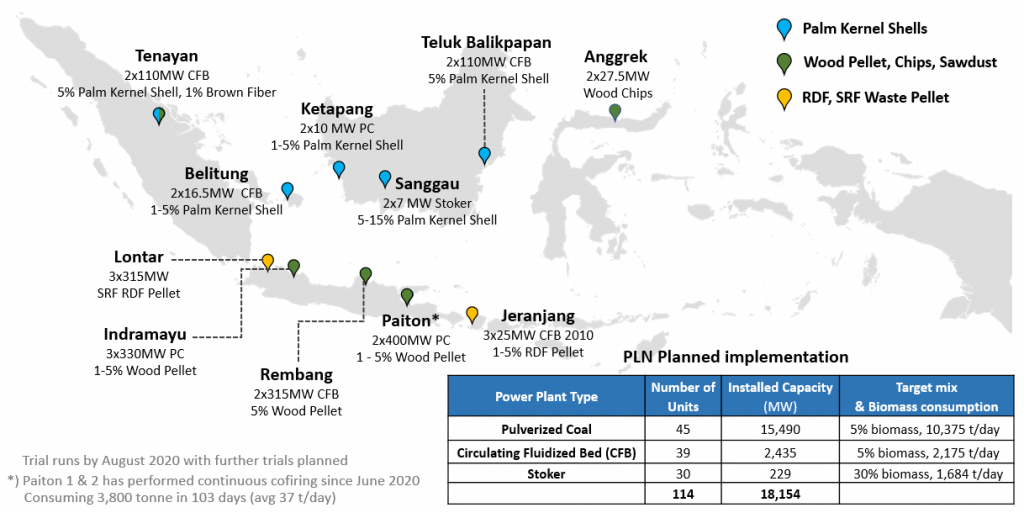

PLN’s cofiring roadmap proposes to migrate its 114 existing coal-fired power plants to cofiring by 2024. The plan includes “feedstock increases” between 2021 and 2023. The cofiring plan, advanced by the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (MEMR), will require nothing less than the creation of a large-scale biomass industry, to provide stable cofiring fuel supplies anywhere between 4 to 9 million tonnes annually.

Cofiring Initial Trial Runs

Source: MEMR, PLN. MEMR Presentation on biomass. Figures presented only include PLN CFPPs.

Biomass Fuels Comparison

Source: van Niekerk, 2017, presented at joint IEA CCC/EPPEI workshop.

IEEFA’s analysis shows MEMR’s framework for biomass cofiring should be adjusted to reflect key technical and economic variables.

Principal Cofiring Challenges

Source: IEEFA.

A) Low-ratio cofiring is a mature technology. Yet, its application globally remains small in comparison to other technology options. This raises the question of economic feasibility.

Cofiring has been utilised since the late 1990s in a number of countries. The primary barriers to its acceptance have remained largely unchanged over the past 20 years. Those barriers include:

- The premium price of biomass on an energy-adjusted basis.

- The ability to establish stable feedstock supply chains.

- A range of technical challenges that that will likely place an operational and financial burden on PLN.

Unless these issues can be addressed, it is not clear that this technology can scale efficiently in Indonesia’s diverse geographies. Despite significant investment, it’s notable that neither the United States nor China has managed to develop sizeable cofiring operations despite their enormous biomass potential, large coal-fired power plant fleets, and strong power plant technological base.

Comparison to biomass applications in other countries — such as UK — should also be treated with care. In 2019, policy-based funding support toward UK’s largest full-biomass power plant amounted to more than £700 million.

B) Policy interventions and incentives have been instrumental to the development of cofiring elsewhere. Does PLN have the resources to support this initiative?

Policy support such as Feed-in-Tariffs (FITs) and Renewable Portfolio Standards (RPS) have been critical in the development of cofiring in other countries. Currently, no planned policy incentives have been introduced in Indonesia.

FIT vs RPS

| Scheme | Mechanism | Pricing & Challenges |

| Feed-in Tariffs (FiT) | A price-based scheme, providing a guaranteed price for eligible renewable energy producers. | Pricing determined by government. Insulate investors from revenue risks. Heavy burden on government and discourages continual cost reduction. |

| Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) | A quantity-based scheme that requires a specific proportion of electricity to be generated through RE sources. Such electricity could be generated by the utility companies, purchased from other parties, or met through the purchase of Renewable Energy Credits (REC). | Market pricing, based on Renewable Energy Credits, a tradeable instrument issued for RE power generation. Less burden on government, higher price volatility and monitoring efforts. |

C) To understand the full costs of cofiring, it is crucial to analyse the ‘total impact’ of cofiring on PLN’s operational and financial results.

Analysts know that cofiring cannot be evaluated on the basis of fuel costs alone. Key stakeholders will need to evaluate the total costs resulting from the way that cofiring will change the operational profile of coal-fired power plant, resulting in increased ash deposition, corrosion, and reduced fuel efficiency.

Non-conventional wood biomass such as sawdust could offer a lower cost fuel, but feedstock options need to be anchored to a viable supply plan and a sound technical assessment. Proper examination of waste-based refuse derived fuel (RDF) specification is even more critical given its potentially challenging properties for cofiring.

D) Presenting a clear cofiring roadmap that addresses the market challenges will be crucial to gain trust from both public and private sector investors. Constructing a targeted priority plan would likely be more beneficial than casting a nation-wide net.

Putting forward pilot cases that are heavily funded by grants and CSR funding does not build confidence in the ability of cofiring to attract major investments. Transparency on the cost of viable and scalable feedstock supplies is necessary, along with clarity on the demand centre, and demand forecasts.

“The challenge lies in its economic feasibility.”

Given the inflexibility of Indonesia’s generation mix, it is not surprising that cofiring could be viewed as one of the few technically feasible strategies for increasing bioenergy use. The challenge lies in its economic feasibility. The claim that biomass could be obtained at a price lower than coal is a commendable ambition, but it has generally not been possible in other countries which implement cofiring based on careful selection of biomass.

The biomass industry is a policy reliant industry with high uncertainty. Success hinges on government and PLN’s long-term commitment to make it viable.

The recent growth in Indonesia’s wood-based biomass industry is a result of increased international demand for biomass based on premium pricing. Whether a market would develop to respond to the low-cost biomass demanded by PLN remains an open question.

The challenges of feedstock market creation should not be underestimated.

The fuel flexibility offered by cofiring — the ability to switch back to coal — reduces PLN’s biomass supply risk, something that has dragged down many biomass power generation projects.

Such flexibility, however, can discourage potential investors looking for a secure market opportunity. Long-term purchase contracts would likely be needed to help build a critical mass for the biomass industry. At the same time, if long-term contracts are required, it could result in the same type of “lock-in” risk that PLN already faces with coal and gas suppliers.

Stakeholders need to critically examine the scale at which cofiring could realistically be achieved with respect to the bold targets proposed by MEMR.

The projected rise of Independent Power Producers (IPP) and the decline of PLN power generation share in the coming decade would also need to be considered in evaluating the full impact of the cofiring programme.

A targeted deployment plan focused on demonstrating commercial viability and PLN’s willingness to support long-term purchase agreements would send a stronger positive signal to attract major investments for the biomass industry.

“Indonesia has the potential to become a biomass industry powerhouse, and the cofiring ambition could be a starting point to spark its development. Such ambition, however, could only be established with sound planning and the transparency needed to support a stable long-term market.”

Read more on similar coverage from FuturArc:

Five reasons to be optimistic about clean energy in 2021 by Marcel Alers, Head of Energy, UNDP

The energy sector, still dominated by fossil fuels, is the largest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions. We know we need to switch to sustainable energy. Yet, despite progress, we are not on track to meet our climate goals and achieve Sustainable Development Goal 7: universal access to clean, affordable and reliable energy. Much more needs to be done.

Renewables should be focus of Vietnam’s Draft PDP8, not coal and gas by Melissa Brown

Many conventional coal and gas-power projects failed to progress during the development process, only managing to meet half of the targeted capacity for 2016–2020. Solar power developers, on the other hand, over-delivered by five times, and they have done so in a fraction of the time. The evidence was clear to inform the next stage of Vietnam’s power development.

Expandable House

The expandable house (rumah tambah in Bahasa Indonesia, or rubah for short) is a component of the Tropical Town project, and is designed as a sustainable response to the challenges of rapidly developing cities in monsoon Asia.

FGLA 2019 Winner: Sekolah Indonesia Cepat Tanggap

The practice of architecture needs to move away from visual aesthetics that have long become the dominant aspect, and should be more inclined to the performance that could support health and safety of the occupants during this pandemic situation.

Read the full report: Indonesia’s Biomass Cofiring Bet – Beware of Implementation Risks

Read the press release in Bahasa: Mengalihkan PLTU ke Cofiring Biomassa Bukanlah Jawaban Pamungkas untuk Mencapai 23% Energi Terbarukan

Putra Adhiguna is an energy analyst with 15 years of experience managing F500 organisations in the energy sector and leading various high-profile projects. He holds an engineering degree from Institut Teknologi Bandung and a Master’s degree in public policy from LSE.

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues.

Previously Published Commentary, Online Exclusive Feature

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older commentaries.