Habitat ’67: Critique on a Classic & Its Modern Interpretations

March 17, 2022

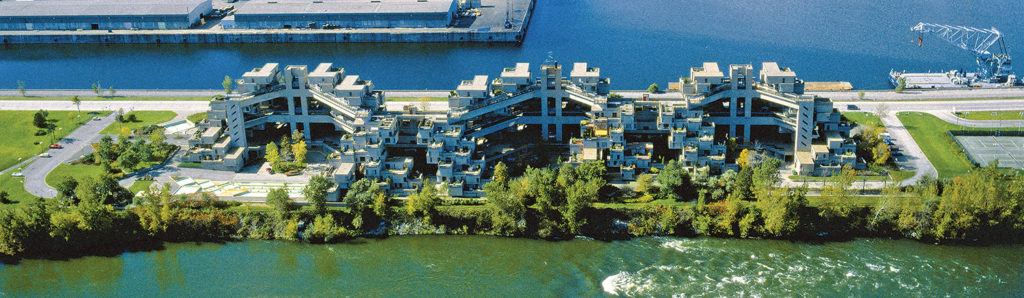

Aerial view of Habitat ’67 as seen from the back, showing its structural core and connecting corridors. Photo courtersy of Safdie Architects

Habitat ’67 is perhaps one of the most recognised and iconic modern housing complexes around the world. The Israel-born Canadian architect Moshe Safdie first developed the concept of Habitat ’67 for his thesis while studying in McGill University in 1961 and submitted the project to Montreal Expo 67 two years later, while he was still working in the office of architect Louis I Kahn. Safdie got the inspiration to design Habitat ’67 as a response to the grim reality of apartment complexes and unsustainable urban sprawl that defined much of the 1960s in North America. Housing architecture in those days was mostly either tall brutalist buildings with apartments stacked on each other without common spillages or suburban row housing with front and backyards but without the vibrancy of streets to look over.

With Habitat ’67, Safdie did more than just combine the two, resulting in a unique concept in urban living that will inspire generations to come. The initial master plan of Habitat ’67 was much bigger in scale—over 1,000 residences along with common amenities like a school and shop—than the built 158 houses in 12-storey interconnected structures.

Photo by Jerry Spearman; courtesy of Safdie Architects

Photo courtesy of Safdie Architects

Top: Moshe Safdie; Bottom: Construction in progress

Close-up of the terraced apartment spaces. Photo by Sam Tata; courtesy of Safdie Architects

The building, which has been given heritage status today, was the embodiment of Safdie’s expression “for everyone a garden”. Although the socialist underpinning of the concept is still debated in the sense of who it was actually meant for—the working class or the middle class—it will not be an exaggeration to say that it was never meant to be luxury living to be experienced by the riches of the city. Safdie truly wanted to make the experience of urban living more enjoyable for everyone, advocating for more space and light for every city dweller. However, like every architect of the generation before him, Safdie made the same mistake of thinking that good design alone is enough to translate to equality and equity in the distribution of housing.

RELATED STORY: Main Feature | Homes, not Houses

The spiralling cost of construction made Habitat ’67 a white elephant for all the parties involved. Adele Weder, a Canadian architect and journalist, wrote in detail about the failings of Habitat ’67 as a ‘low-cost’ housing in The Walrus magazine in 2008. The high cost was mainly attributed to the structural system of the complex, which needed each component to be prefabricated in a factory that was especially set up for the project. Looking back, the idea was ahead of its time since prefabrication was many years away from becoming mainstream. However, it is poignantly clear why Safdie—a man in his twenties then with a vision—pushed for the technology even with the rising cost. Prefabrication of all the components would have helped Habitat ’67 proliferate around the world, which was the core value and vision of his thesis.

After more than five decades of Habitat ’67, many other versions or iterations have come up around the world, but not in the same way Safdie—or his thesis—would have intended.

ALTAIR RESIDENCES

COLOMBO, SRI LANKA

The tower is made up of diagonally jutting balconies overlooking the city. Photo by Space80; courtesy of Safdie Architects

Section

The recently completed Altair Residences brings modular apartment living to the Indian subcontinent. The skyscraper, which appears to have one tower leaning towards the other against the picturesque backdrop of Colombo, has 400 residential units overlooking the Beira Lake. Taking its cue from the terraced gardens of Habitat ’67, Altair Residences has a communal sky garden atop the 63-storey tower.

Marketed to the ultra-rich class, the units, with areas ranging from 1,500 square feet to 4,000 square feet, are currently being sold at the price of USD500,000 to USD700,000. According to an article published by Financial Times, most of the housing market in Colombo—the capital of Sri Lanka—caters to Sri Lankans living abroad, foreign buyers and locally-based high net-worth individuals, resulting in empty housing stock along with shortage of affordable housing. Looking at the housing scenario of a developing nation like Sri Lanka, Altair Residences seems to have come far away from the original inspiration that challenged the existing housing norms and pushed the boundaries of the very idea of apartment living—it neatly replicates the architecture of Habitat ’67, but without the core values that created the architecture in the first place.

PROJECT DATA

Client

Indocean Developers Pvt Ltd

Completion

September 2021

Area

139,355 square metres

Associate Architect

Design Team 3

Structural Design Consultant

Derby Design

MEP Designer

CKR

Specialist Lighting Consultant

Studio Lumen

Vertical Transportation Consultant

Barker Mohandas

Fire Engineers

FPC

Wind Analysis Consultant

RWDI

Landscape Consultant

P Landscape

QORNER TOWER

QUITO, ECUADOR

Qorner Tower’s irregular façade hides behind it a perimeter concrete frame that is designed to withstand earthquake damage. Images courtesy of Safdie Architects

Section

Qorner Tower is a 24-storey residential building currently under construction in the city of Quito—the capital of the South American nation of Ecuador, known for being surrounded by active volcanoes. The artistic impressions and renderings of the building appear to be a playful arrangement of cuboids spilling into terraced gardens looking to break the monotony of tall grey buildings that make up most of the modern construction in the city.

Qorner Tower does a good job of retaining the playfulness of Habitat ’67 through the play of volumes opening into terraced gardens, which are designed to eventually mimic the greenery outside and function as ‘plantscrapper’ to enable offsetting its carbon footprint later. However, there has been no data to prove how and when this will happen. For a building of its scale—127,000 square feet of built space—it seems like the project will have to do more than just natural ventilation and vertical plant wall to be a sustainable endeavour, especially in an increasingly climate-vulnerable world where the novelty of skyscrapers is soon wearing out.

PROJECT DATA

Client

Uribe and Schwarzkopf

Expected Completion

Spring 2022

Area

127,000 square feet

Design Architect

Safdie Architects

Associate Architect

Uribe and Schwarzkopf

Landscape Architect

Greenstar Landscape

HABITAT QINHUANGDAO

CHINA

Exterior perspective. Photo courtesy of Kerry Properties

Section

Habitat Qinhuangdao is a high-density housing complex situated 200 miles away from Beijing, the capital of China, between the city of Qinhuangdao and the coast of Bohai Sea. It is organised into a series-linked residential blocks along the shore. The 16-storey-high blocks are designed to accommodate the growing urban population of Qinhuangdao, who want to stay connected to the city and yet enjoy the countryside.

The complex is marketed to the burgeoning middle class of China as relief from the cramped and closed urban centres. However, the units are priced on the higher side of the spectrum, pegging the development as middle- to high-income housing. Phase II of the project will add 1,000 units distributed across two 30-storey terraced buildings, doubling the capacity of Phase I, which opened in 2017.

PROJECT DATA

Client

Kerry Properties

Expected Completion

2024 (Phase 1 of the development completed in 2017)

Design Architect

Safdie Architects

Local Design Institute

China Shanghai Architectural Design & Research Institute Co. Ltd

Landscape Architect

WAA Landscape Architects

Area

Phase 1: 152,450 square metres;

Phase 2: 244,000 square metres;

Sales office: 5,500 square metres

Façade Consultant

Konstruct West Partners

Façade Design Institute

Zhe Jiang Zhong Nan Construction Group Co., Ltd.

Interior Designers

BC&A International Ltd.; Yasha

Landscape Design Architect

SWA Group

Landscape Design Institutes

Ager Group; DQLand

Lighting Design Consultants

Lam Partners; Brandston Partnership Inc.

[This is an excerpt. Subscribe to the digital edition or hardcopy to read the complete article.]

Bhawna Jaimini is a writer and urban practitioner based in Mumbai, India. Trained as an architect, she currently works with Community Design Agency on projects that seek to improve the built habitats of some of the most marginalised communities in India’s urban areas, using participatory tools. She is deeply passionate about gender rights and using architecture and design to address issues of social inequality and inequity in these areas.

READ MORE: In Conversation | Safdie Architects: Charu Kokate

Read more stories from FuturArc 1Q 2022: Housing Asia!

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues.

Previously Published Showcase

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older commentaries.