In Conversation with Avneesh Tiwari & Neha Rane of atArchitecture

March 27, 2018

Avneesh Tiwari & Neha Rane

Gold winner of the 2017 LafargeHolcim Awards, Asia Pacific region, atArchitecture is a Mumbai firm founded by Avneesh Tiwari and Neha Rane in 2013. Born and raised in Mumbai, the pair met while studying at the Sir JJ College of Architecture.

Tiwari went on to work with Gurjit Singh at Matharoo Associates, and currently lectures as a visiting professor at the Rachana Sansad Academy of Architecture and Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute for Architecture and Environmental Studies in Mumbai, as well as running atArchitecture.

Rane has worked with HCP Design, Planning and Management Pvt Ltd (HCPDPM) and Vastu Shilpa Consultants, has specialised training in earth architecture from the Earth Institute, Auroville, and is now head of design at atArchitecture.

HB: Tell me about your firm’s philosophy.

HB: You’ve just won Gold at the LafargeHolcim Awards for your Home for Marginalised Children in Thane, India. How did this project come about?

AT: Around four years ago, we decided to use our practice to give back to society, so we approached a handful of NGOs in Mumbai, offering free architectural services. Our client, CORP, was one of those who responded. The project was delayed for a while due to a shortage of funds, but we are planning to start construction in the next few months.

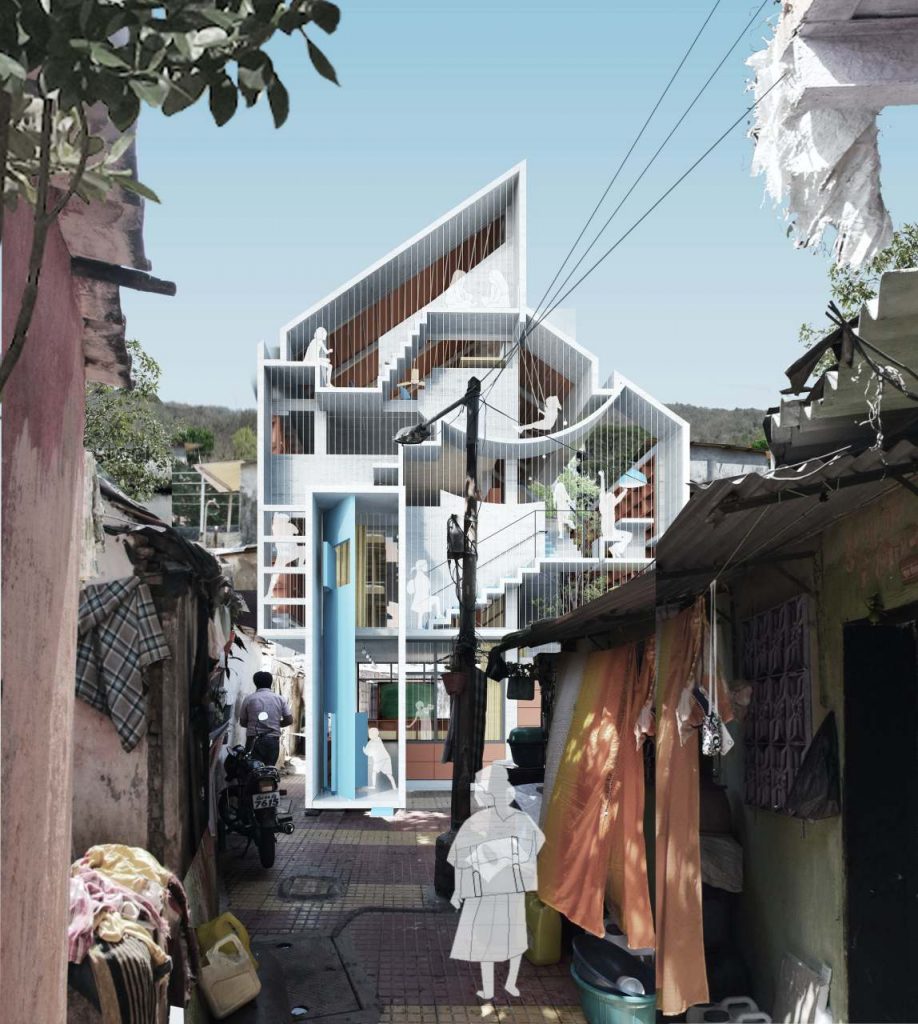

HB: The awards jury nicknamed the project the White Rabbit because of the playful, whimsical feeling of the design, which is very much oriented towards the children’s experience—how did you approach this?

AT: This really arose from the project itself. When we went to the site for the first time and started interacting with the kids there, we noticed that most of the current space was actually occupied by storage, so there were 30 people in a 600- to 700-square-feet area with no spillover space. Because of the limited area, the kids were not behaving true to their age. Imagine being a kid, just sitting in one corner, doing nothing. This is what the project evolved from—we wanted to give them the freedom to act their age, to give them their childhood back.

Part of this is the idea that the users will transform the space. For instance, the elevation we designed will be completely different when it is up. As the façade is inhabited and interpreted by the users in their own way, it will take on its own character.

HB: So essentially, you want the building to act as a canvas, allowing the users to create their

own space.

AT: Absolutely. The existing structure is only a small building with drywall and small openings. We wanted to provide them with freedom and privacy, as well as the ability to interact with the neighbourhood—the building should not show its back to the slum. So the two recreational areas become places of interaction, like the veranda of a house where the kids can play, sit, read, do whatever they like, while the façade interacts with the slum and becomes a part of the overall slum fabric.

HB: How did you find the community around the site? Were they receptive to the project?

AT: From our interaction with the administration and the caretakers of the slum, there is no problem. The current structure has already been there for five, 10 years now and everyone is ok with it.

NR: It is a community

To read the complete article, get your hardcopy at our online shop/newsstands/major bookstores; subscribe to FuturArc or download the FuturArc App to read the issues!

Previously Published In Conversation

Contact us at https://www.futurarc.com/contact-us for older interviews.